If you search the term “rodent” on the internet, it’s telling. Besides a dictionary definition (above), the web pages include health cautions, extermination services, how-to traps, and more. Apparently, lots of people regard these animals as unwelcome, dirty pests. Dig deeper, and you’ll find a rich wild world of amazing animals with intriguing lifestyles.

What is a rodent?

A gnawing mammal of an order that includes rats, mice, squirrels, hamsters, porcupines, and their relatives, distinguished by strong constantly growing incisors and no canine teeth. They constitute the largest order of mammals.

Four out of 10 species of mammals are rodents in Colorado and worldwide. In sheer numbers of mammals alive at one time, rodents probably outnumber all other mammals combined, including people.

Some rodents are vegetarian, gnawing away at everything from tree bark to cattails to succulent seeds. The grasshopper mouse — a carnivore — consumes a wide variety of insects. Some rodents, alas, make meals of bird seed from feeders, trash from carelessly filled garbage cans, and insulation from wiring. That’s in part why they get a bad rap.

Colorado is home to almost 60 rodent species. Many of them are small, secretive, and seldom seen as they scurry along runways through the grass, tunnel beneath snow, or den underground. Some small rodents were recognized as living here only after their teeth or bones turned up in the scat of predators and the pellets of owls.

Rodent teeth are remarkable. They grow continually, and the animal gnaws all the time to sharpen and trim their chisel-like incisors. One weather-whitened skull revealed still-orange-coated incisors, but the teeth were loose and when pulled, came out of the tooth sockets as semicircles of teeth in reserve.

Rodents have been around for roughly 65 million years. Globally, they live everywhere except Antarctica. In Colorado they’re found from tundra (think of yellow-bellied marmots) to wetlands (beavers and muskrats); from woodlands and treetops (fox squirrels, chickarees, Abert’s squirrels, chipmunks, and porcupines) to grasslands (prairie dogs, voles, and mice).

Small rodents — mice, voles, and chipmunks — occupy the lowest rungs of the “food chain,” a prey for foxes, coyotes, badgers, weasels, owls, hawks, and snakes. If it were not for this predation, ecosystems would be overrun with small rodents. Deer mice can produce from one to 11 babies (they average four to six) in each litter, and litters are produced year-round, from five to 10 litters a year; do the math!

What follows is a sampler of watchable local rodents

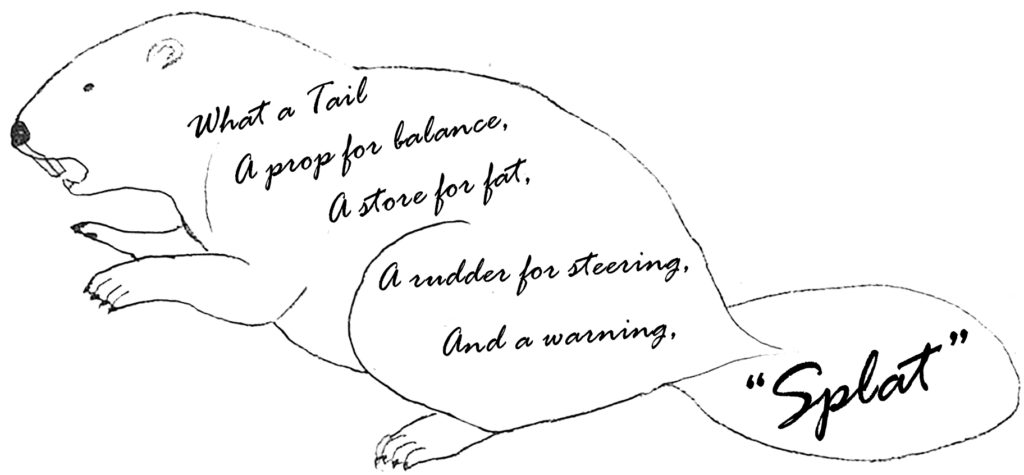

Our largest rodent (up to 50 lbs.) is the beaver. It mainly eats bark, buds, and leaves and twigs of aspens and willows. Its flat tail is amazingly versatile. (Note: the similar but smaller muskrat has a skinny, side-to-side moving tail.) The beaver’s legendary dam building skills slow up water runoff and help prevent deep gullies from forming.

The porcupine is Colorado’s second-largest rodent. Active year-round, it lives by eating the bark, buds, and foliage of shrubs and saplings. Look for map-shaped patches left after bark-stripping. Their quills serve as a superb defense against most predators, but porcupines cannot “throw” their quills; they merely detach easily.

Arguably the cutest rodents are chipmunks. They may hold seeds in their front paws as they eat, or stuff seeds into their pouchy cheeks and scurry away to hideouts safer than open ground to chow down.

The tassel-eared Abert’s squirrel inhabits ponderosa pine woodlands, where it feasts on inner bark from the pines’ tender terminal branches, scattering tell-tale short, peeled twigs beneath favored eating trees.

Colonial black-tailed prairie dogs, whose extensive underground tunnels are habitat for various other creatures, is a “keystone species” vital to its ecosystem. Without prairie dogs the whole grassland web of life might collapse. Prairie dogs are vocal, using a complex language of yips and barks to keep the group cohesive and warn colony-mates in detail of predators and intruders.

Smart, agile, and devious, the fox squirrel is an immigrant, having trekked here from the east along treed waterways. It’s now at home in people-places. Watch it tight-rope along wires to cross highways, scurry down trees with amazing agility (it rotates its hind feet to aid swift descents), and raid almost every bird feeder ever invented.