Cattails. Rushes. Sedges. They’re the big three of wetlands, flowering plants that dominate marshy areas. Yet to many of us, they are little-noticed green fringes along the margins of lakes and ponds.

These plants offer food, shelter, and homesites to mammals, birds, insects, and other creatures living in and around ponds, marshes, and rivers. They help keep ponds clean, filtering out silt and impurities flowing in from towns, farms, and gardens.

What Are These VIPs?

Cattails are tall, wet-loving green plants in the botanical family, Typhaceae. They grow and spread—from strong rhizomes partly floating or rooted in mud. Our local species are broad-leaved cattail (Typha latifolia) and narrow-leaved cattail (Typha angustifolia). Both have sturdy, flat-bladed leaves from three-to nine-feet tall. You might wonder how such leaves withstand high winds. The secret lies in strong, crisscrossed, internal supports comparable to aircraft wing-struts.

Look for furry brown, hotdog-shaped spikes (those are the female flowers that produce seeds) and above them straggly male flowers that produce loads of pollen. Broad-leaved cattails have female and male flowers jammed close together on upright stems. Narrow-leaved cattails have an obvious gap between female and male flowers. When the seeds are ripe, a squeeze of the “hotdog” or a strong wind will release thousands of potential new plants. In the past, this fluff was used to stuff pillows, beds, and even life preservers.

Cattails are prolific and may eventually fill shallow open waters. Hungry muskrats and water birds may cull them, but nature is never static, and changing water levels and animal-use patterns may lead to ponds filling in—that’s succession. Example? When the boardwalk at Walden Ponds Wildlife Preserve was built in 1991, it was at the water’s edge, and people watched muskrats and northern water snakes as they swam beneath it. Now, the idea of fishing from the walkway is absurd, even if it were allowed!

Green fringes continue to be great homesites. Female red-winged blackbirds construct their nests of stringy plant fibers—grass, cattails, and even tree bark—building the cup-shaped homes around several upright cattail stems not far above the water. Imagine a hanging basket woven tightly around ever-moving stems, created with beak and claws—it’s an incredible feat.

Sedges have edges.

Rushes are round.

And grasses have knees (nodes)

that bend to the ground.

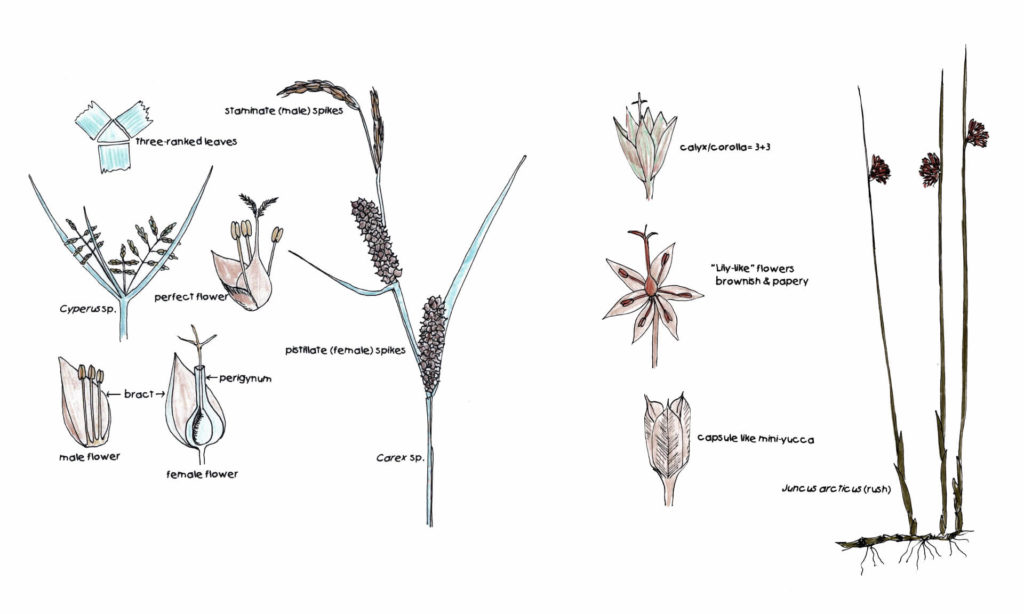

This rhyme aims to identify the other two wetland VIPs, but do not take it too seriously. Sedges usually have stems with edges that are triangular in cross-section (try rolling the stem between your fingers) and have three-ranked leaves.

Many sedge species populate wetlands, but others thrive in dry landscapes. It is in high-country wetlands that sedges dominate. Within the sedge family, the genus Carex has more species in it than any other flowering plant genus in Colorado—more than 100 kinds to identify. Carex flowers are tiny, not showy. Some are just small clusters of pinhead-sized granules. Others are long and gracefully drooping. Some have female and male parts all-in-one (botanists call these perfect flowers). Others have separate male and female flowers. Either way, there are no showy petals, just papery sheaths around the working parts. Dense “edge-veg” consistently includes sedges.

Members of the rush family (Juncaceae) are frequently described as “grass-like,” but their stems do not have nodes (knees). And to complicate things, their stems can be round—or flattened! Many have tufty clusters of tiny, undistinguished flowers issuing from the side of the stem. They seem to thrive in slightly deeper water than cattails where both occur, but this is observation is only an impression. At Mud Lake in summer, the wide swath of rushes is brilliantly alive with darting dragonflies.