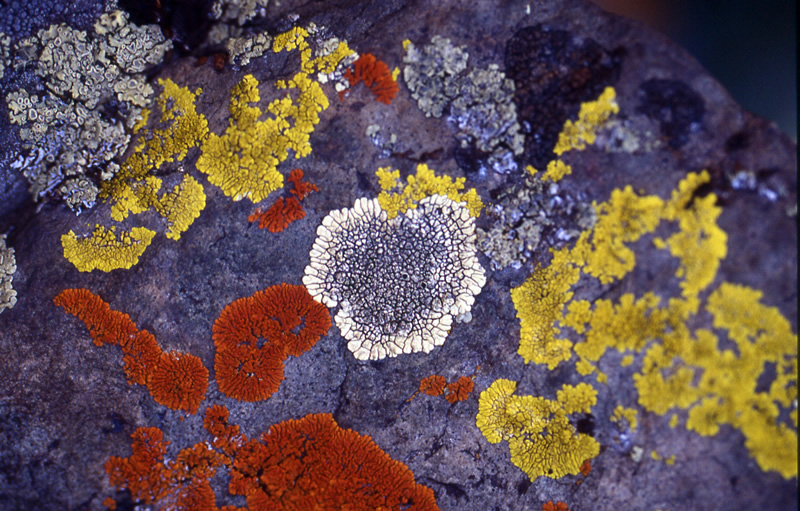

On a recent hike in the foothills I took a short break and sat on a flat rock. It was an ordinary rock, but what’s ordinary when you really take a good look at it? Idly, I started counting the types of lichens I could distinguish. There were five! Continuing on my walk I couldn’t stop looking at the lichen diversity around me. They seemed to be the most common, prolific and ubiquitous part of the ecosystem. I started wondering about this often-ignored life form. As the tabloids say, “inquiring minds want to know,” so I started investigating.

Lichens are fabulously interesting. They are a little like a three-layer cookie. The outer layer is a fungus, the middle layer is either a green or blue-green algae, and the lower layer helps it adhere to whatever surface it’s on. And lichens can grow on nearly any surface, even some you’d never think of: rocks, trees, soils, even glass, metal, an insect or two and one species of tortoise.

Any Place Can Be Called Home

Lichens grow in nearly every terrestrial environment from pole to pole. They grow in extreme conditions that preclude most other life forms. How do they accomplish this extreme biological feat? The complex relationship between the lichen’s fungus and its alga provides the answer. The algal component photosynthesizes food for the lichen. The outside fungal layer shields the algal layer from too much sun exposure, filters water down to it and provides a habitat in which the algae can live.

This makes the lichen pretty self-sufficient. Lichens can colonize habitats that are too extreme or barren for any other organism, even rocks themselves. They are able to survive without water for long periods, and can attach to almost any substrate. Lichens carry their own food with them. They can reproduce sexually, asexually or both. Some lichens can live up to 4,000 years. No wonder they are everywhere!

Low Profile, Big Role

Though lichens fly entirely below the radar of most people, they nonetheless provide crucial benefits to the environment. They contribute to the first stage of weathering the rocks on which they live, creating tiny crevasses into which water’s freezing/thawing action can permeate. Rock disintegration provides the raw material for building soil. In cryptobiotic soils, lichens bind soil particles together. These fragile, crusty soils trap blowing dust, prevent erosion, and add nutrients. The decay of dead lichens contributes nitrogen to the soil. Some even host nitrogen fixing bacteria.

Caribou, mule deer, mountain goats, moose, and pronghorn all use lichen for forage, especially in winter. Birds incorporate them into their nests. Some native tribes, especially in boreal areas have concocted many ways to prepare lichens for human consumption. Lichens have been used to make dyes for thousands of years, and they can be used in making perfume. Some have medicinal qualities. If that were not enough, scientists can even use lichen growth patterns for dating stone structures, similar to dendrochronology.

Lichens absorb whatever is in the air around them, including common pollutants like sulphur dioxide (produced by burning coal), fluoride, ozone, hydro-carbons and some heavy metals. This ability makes them very sensitive to changes in air quality and important indicators to what is in the atmosphere, making them the canary in the coal mine for atmospheric degradation.

different species share this rock. They have existed on earth for at least 400 million years, giving them lots of time to diversify.

Hardy, But Not Invincible

Human activities have had devastating effects on lichen health. The usual culprits: urbanization, other types development, habitat fragmentation and pollution destroy their environments. Hiking, over-grazing, even rock climbing can have severely detrimental effects on lichens. In some areas lichens have been almost completely eliminated.

Next time you’re out hiking, open your eyes and notice them. Take your hand lens with you on your next hike and pause to examine them up close. They are colorful, beautiful, and wondrous. There are so many reasons to like lichens.