Sounds may first alert birders to the presence of a downy woodpecker. A sharp “pik, pik,” or a shrill, descending whinny call catches your attention. A slow and intermittent “tap-tap-tap” hints the bird is feeding. A fast (up to 20 hits a second), insistent drumming may echo from a nearby tree, power pole, or even a metal chimney pipe (to ear-shattering effect) as the bird communicates, tries to attract a mate, or claims territory. The noises suggest a large bird. But the downy, our smallest woodpecker, is only 5 ½ to 6 ½ inches, somewhere between the size of a sparrow or robin.

These small insect eaters nimbly circle tree trunks and branches to probe for edibles in the bark—and equally nimbly vanish around the trunk when you try to look at them! When they leave for the next food tree, they move with undulating flight.

Downy woodpeckers are found in woodlands, orchards, parks, riparian areas, and leafy back yards, and although never numerous, they are year-round residents.

Look Alikes

They are common feeder birds and will consume black oil sunflower seeds, peanuts, millet, and suet. While feasting, they stay put and allow watchers to study what distinguishes them from their near look-alikes, hairy woodpeckers (which are roughly 1/3 larger than downies).

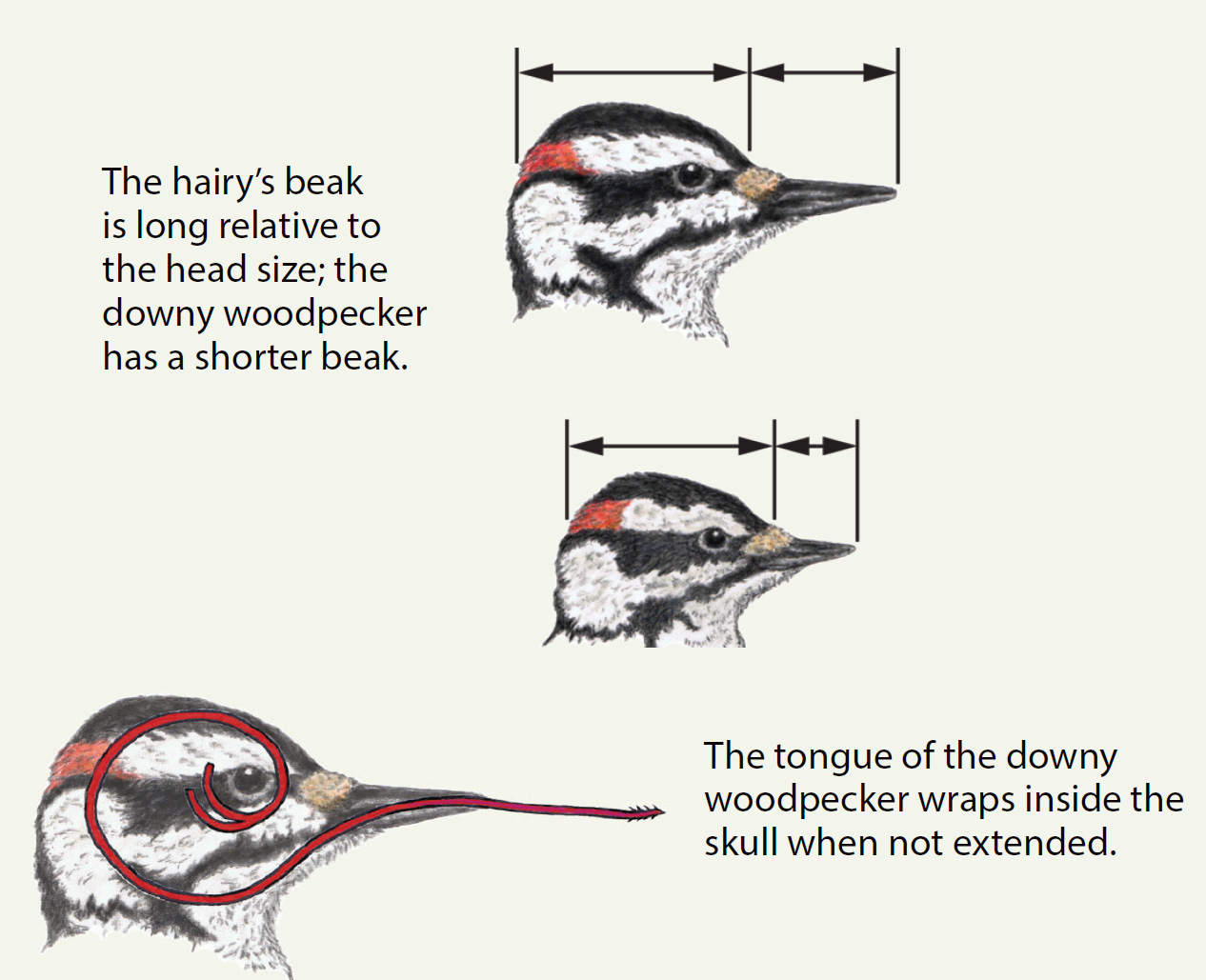

Both species are black and white, males have red on the head, and both species have stiff, pointed tail feathers that help brace them as they spiral up trunks or when they hammer away to get food or chisel out nests. Both species have similar foraging behaviors, although the smaller downies seem to select smaller, slimmer, higher branches, but not always. Both have similar feet with two toes forward, two toes back, to help them climb. How do these two species differ besides size? The best clues are the bill size and shape. A downy has a small, dainty bill, about half the length of its head; a hairy has a heftier, thorn-like bill almost as long as the width of its head from front to nape.

It is said, “Birds of a feather flock together.” Downy woodpeckers don’t flock with masses of their own kind. They only pair with their mates. But in winter, downy woodpeckers do associate with other small birds as they forage, forming loose mixed flocks with chickadees and nuthatches. Many pairs of eyes are an asset in food finding. When predators lurk, some safety comes with numbers. Mixed flocks are aware of all alarm calls—even from other species they travel with—and the whole feathered gang teams up to mob any dangerous intruder. Predators? Think domestic cats, hawks, squirrels, snakes, and rats.

Downy woodpeckers nest in tree cavities. The female lays from three to eight eggs, both parents take nest duty, and both supply food to the nestlings when they hatch and until they leave the nest some eighteen to twenty-one days later.

Built-in Protective Gear

The nest is often excavated from the underside of an angled dead branch or snag and takes a lot of drilling. How can they hammer away without getting concussed? They have thickened skulls with special spongy, shock-absorbing layers around the brain and the eyes.

Anatomy-wise, that’s not the only remarkable feature that these birds have evolved to suit their unique lifestyle. They have bristly feathers around their beaks to trap flying sawdust before the birds breathe it in through their nostrils. Amazing!

That’s not all . . . a downy woodpecker’s tongue is long and barb-tipped (not as long as the flicker’s tongue, which is the bird record-holder!) The tongue wraps around inside the skull when not extending to pry out bark insects, then flicks out far beyond the bill tip when feeding.

This small, familiar bird is a champion in so many ways and it is definitely worth a second and third look!